Chances are, you weren’t born into wealth and luxury. But, like every other American, you hold a stake in an immense treasure: 828 million acres of public land. [1] You carry a deed to some of America’s most beautiful natural wonders—Yellowstone, the Great Smokey Mountains, the Grand Canyon, and more—regardless of your personal wealth or social status. It is a modern miracle that the American public enjoys these vast acres—equivalent to the entire landmass of India [2] —for hiking, sightseeing, and other outdoor recreation. This concept is deeply American: making land, recreation, wildlife, scenery, and solitude available to all. [3]

Unfortunately, large swaths of this public land are inaccessible. Although the outdoor recreation community has long been aware of public land parcels that have no legal access, [4] until recently, neither outdoor recreationists nor the federal government knew exactly how much public land is inaccessible to the public. [5] But in 2018, private businesses and nonprofit organizations worked together to discover 16.43 million acres of “landlocked” public lands spread across twenty-two states. [6]

These landlocked public lands lie untouched by public roadways and lack access easements—leaving them inaccessible and off-limits to the public. As a result, these public lands are circumscribed behind private property, along with their accompanying hiking, camping, fishing, biking, skiing, and hunting opportunities. And adjacent private property owners enjoy exclusive benefit of these lands that belong to us all.

Landlocked properties can be categorized in two ways. First, by how they are landlocked: either “corner-locked” or “isolated.” This distinction is fully elaborated upon in Part II, infra, and almost equally divides the landlocked properties as 8.30 million acres are corner-locked and 8.13 million acres are isolated. [7] The second way to categorize the properties is by their ownership: either state or federal. Of the total 16.43 million landlocked acres, 6.35 million acres belong to individual states, [8] while the almost 10 million remaining are managed by federal agencies such as the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) or the United States Forest Service (USFS). [9]

This Note examines the legal and political challenges surrounding America’s landlocked public lands and offers unique solutions to unlock these properties. Part I explains the history behind how and why these lands became inaccessible to the public. Part II introduces the distinctions between corner-locked and isolated landlocked parcels. Part III provides a call to action by examining the cost to society that these landlocked public lands impose via their economic and social opportunity costs. Part IV discusses how the common law doctrine of easements by strict necessity and the public trust doctrine fail to solve the landlocked public lands issue. Parts V and VI examine legislative attempts to unlock these lands, through property acquisitions and other non-acquisition-based programs.

Finally, Part VI evaluates the special issue of corner-crossing on corner-locked properties and argues that the Unlawful Inclosures Act of 1885 (UIA) is an effective tool for combatting trespass claims related to corner-crossing. Indeed, litigants have used this 135-year-old statute to gain access to public land across privately held parcels. The UIA is still good law, and its application in corner-crossing cases would unlock 8.3 million acres of corner-locked property and provide the public with all the economic and social benefits that accompany those vast acres.

Today’s public lands access challenges are rooted in the history of the lands themselves. Congress promulgated 18th and 19th-century policies that governed how newly acquired federal land was to be surveyed and granted to railroad companies and homesteaders as incentives for westward expansion. This Part details that history and characterizes the scope of the landlocked public lands problem. The first subpart provides historical context surrounding landlocked federal lands. The second subpart describes the similarities—and significant differences—that accompany state-owned landlocked lands.

Nearly 10 million acres of federal public land is landlocked and off-limits to the general public. [10] The history behind these landlocked federal public lands is long and tortuous. It includes legislation, judicial opinions, and 185 years of real estate transactions implicating the federal government, state governments, large corporations, and small farmers. To fully understand this history, one must start with the Public Land Survey System.

After the American Revolutionary War, the United States acquired title to the Ohio Country—which included all the land west of the Appalachian Mountains, north of the Ohio River, and east of the Mississippi River. [11] This property windfall required the federal government to confront a new problem, and one important issue was how to measure, divide, distribute, and induce settlement of this newly-acquired territory. In short, the federal government needed to inventory its new land and quickly turn that land into cash. The new Union was deeply in debt from the war [12] —and did not yet have the power to directly tax the citizenry [13] —so it was in desperate need to sell off the Ohio Country to raise funds for the increasingly insolvent government. [14]

The Confederation Congress appointed a committee to design a system for surveying and distributing the Ohio Country. [15] The committee reviewed a few existing survey methods, notably the British “metes and bounds” system from the original colonies. [16] This system defined property lines using topography and natural landmarks. [17] A simple description under this system might read: “From the point on Goodfood Creek’s north bank one mile above the junction of Slab and Coldwater Creeks, north for 1300 yards, northwest to the large standing rock, west to the large oak tree, south to Goodfood Creek, then down the center of the creek to the starting point.”

But this system had issues. First, the obvious: nature evolves. Trees die, storms shift boulders, and floods cause streams to change course. Second, the system’s irregular shapes led to complex descriptions that created legal disputes based on deeds subject to multiple interpretations. [18] This uncertainty was not useful for the large land tracts in the Ohio Country that investors were buying sight-unseen. [19] Investors hate uncertainty. And the government needed more than rudimentary landmark descriptions to induce investment into this new territory.

To address these shortcomings, the committee introduced the Public Land Survey System (PLSS) through the Land Ordinance of 1785. [20] The ordinance required the United States’ Geographer to divide the territory into townships, six miles square, “divide[d] . . . by lines running due north and south, and others crossing these at right angles.” [21] Each township was then divided into one-square-mile sections of 640 acres. [22] In simpler terms, this ordinance shifted from the uncertain “metes and bounds” system to a standardized system using straight lines and set measurements. It divided the land into square “townships” of thirty-six square miles, further divided into “subdivisons” of 640 acres or one mile, and quarter-sections of 160 acres. [23]

The federal government reserved several sections for its own purposes [24] and auctioned the rest. [25] Fortunately, the PLSS’s clarity and defined title system encouraged demand for western lands by giving speculators security in their purchases and minimizing the risk of legal disputes. This fulfilled the government’s desire to convert this untapped resource into revenue. Although Congress intended the PLLS to reduce property disputes, its legacy has created modern-day conflicts between public and private lands that would have been unimaginable in 1785.

Throughout the first half of the 19th century, the United States acquired the American West. [26] For many years, much of this land remained undeveloped. For example, in 1860, Nebraska’s average population density equaled about one person per every five square miles. [27] While the 1848 California gold rush tempted many eastern residents to move west, [28] they faced a choice between three unpleasant travel options: a four-month trek across the continent, a thirty-five-day voyage through the Isthmus of Panama, or a four-month sail around Cape Horn. [29] Many travelers longed for a better alternative.

Although the gold rush reignited interest, discussions about a transcontinental railroad had existed since 1844. [30] The government wanted the West settled, [31] and safe and efficient transportation was a critical issue for settlers. But “northern and southern interests were deadlocked over the route [the railroad] should take. ” [32] A southern route would promote growth in the Southwest and could lead to more slave states. [33] But a northern route would align with the East’s industrial priorities and discourage the spread of slavery. [34] The Civil War removed southern congressmen, paving the way for the northern route approval, and spurred Congress to act. Driven by the need to bridge the logistical gap with California [35] and to move troops and materials westward, [36] Congress passed the Pacific Railway Act of 1862. [37] The Act and its five amendments—collectively known as the “Pacific Railway Acts” [38] —would provide financial support for the transcontinental railroad. [39] The railroad companies needed this support because the venture was too risky and expensive for private investors to move without tangible government inducement. [40] Because private capital was insufficient, the government financed the railroad with the only currency it had—public lands.

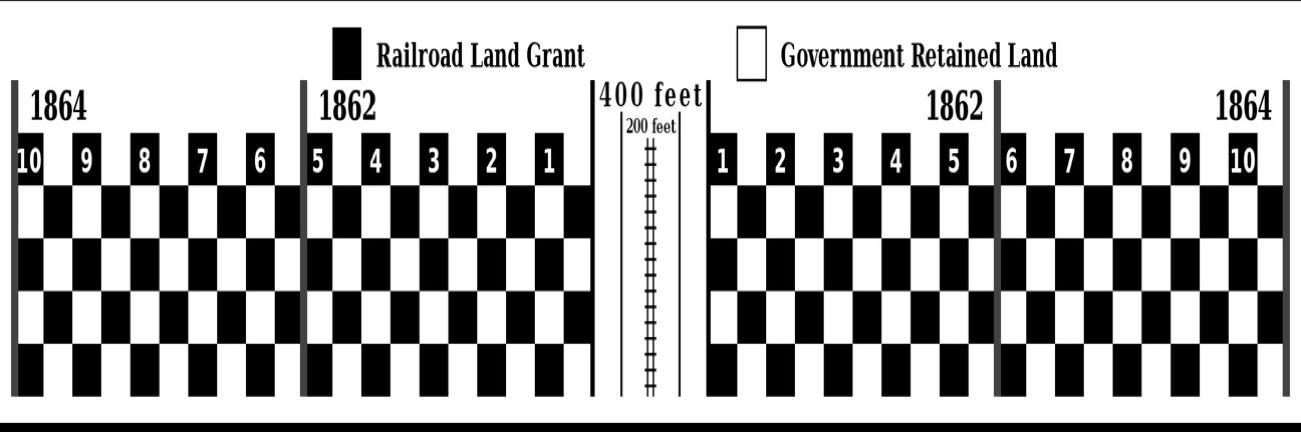

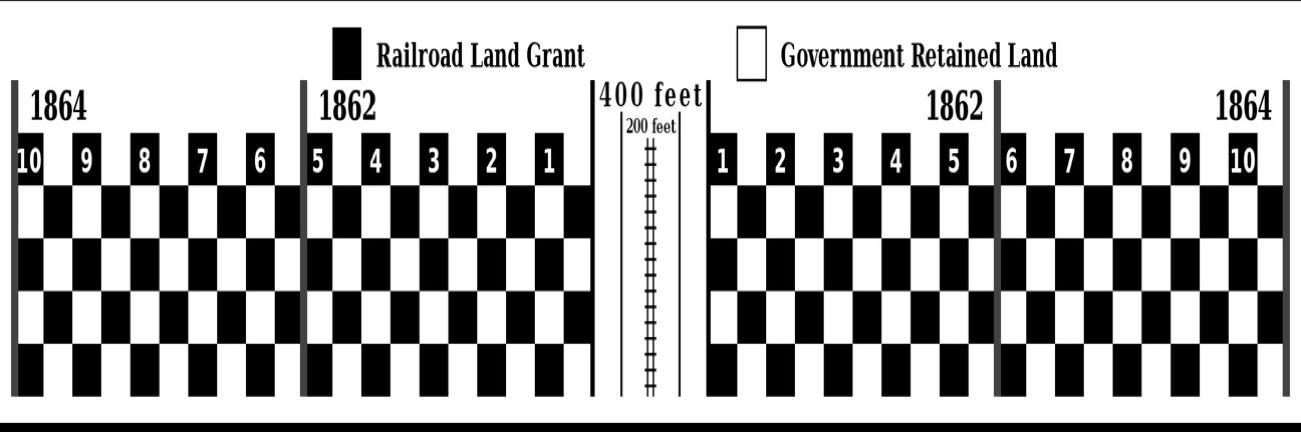

The Pacific Railway Acts granted the railroad companies a 200-foot right-of-way next to the track plus ten sections of land on both sides of the track. [41] Odd-numbered sections were granted to the railroad; even-numbered sections were reserved by the government. The result was a “checkerboard” pattern of public-private land ownership, which still fractures the American West and provides challenges to those who wish to access their public lands.

The rationale behind this checkerboard scheme was simple. Congress hoped the railroad would increase the adjacent public land values, which Congress could then sell at double the price to offset the cost of the subsidy and foster private enterprise. [43] The vision was for parallel development on both private and public land leading to a network of access roads. [44] But this pattern of access roads has not come to complete fruition, and there are still millions of public land acres locked by private land within the checkerboard.

The Homestead Act of 1862 [45] mirrored the Pacific Railway Acts, both in promoting western migration and in landlocking public land. The Homestead Act allowed settlers to claim 160 acres of land from the public sections on the checkerboard. [46] In exchange, homesteaders paid a fee and needed to live on the land for five years, cultivate it, and complete modest improvements. [47]

The legal process was simple. First, the settler applied for a homestead and paid a fee. [48] After a land agent checked for previous ownership claims, the five-year residency began. [49] When the five-year period was complete, the homesteader “proved up” the claim by providing evidence that he had developed the land. [50] After the homesteader proved his claim and paid an additional fee, the Government Land Office issued him a deed of title known as a “patent.” [51]

Congress passed variations of the Homestead Act throughout the 1870s, [52] and any U.S. citizen could receive 160 acres of land. [53] The Acts spurred western migration, increased economic development, and helped make the transcontinental railroad a success. As formerly public sections of the checkerboard were subdivided and converted to private land by settlers, 270 million acres were transferred from the public domain to private homesteaders through the Homestead Act. [54] But there were unintended consequences. As settlers prioritized the best lands, vast tracts of public land were isolated within private boundaries. Much of that public land is still inaccessible today.

When seeking legal solutions to unlock landlocked public land, it is important to understand both the ownership (state or federal) and how the properties are landlocked. In fact, nearly half of America’s landlocked public lands are corner-locked, while the rest are isolated. The legal strategies available to unlock these lands can turn on this distinction.

Isolated parcels are like public-land islands in a sea of private land. These parcels are completely surrounded by private property. In contrast, corner-locked parcels stem from the checkerboard pattern that the PLSS and Pacific Railway Acts created. [55] Where four sections meet, they form a point defined by the intersection of two boundary lines—one running north-south, one east-west. One court described this intersection as “like a point in mathematics . . . without length or width.” [56] This should, in theory, allow a person to step from one section to another without trespassing—a concept known as corner-crossing. [57] Instead, at every point where four squares meet, there is a property corner ripe for controversy because many private landowners consider corner-crossing a trespass.

If corner-crossing were legal, over half of the 16.43 million acres of landlocked land would be unlocked. In fact, 27,120 landlocking corners create 8.3 million acres—the equivalent to almost four Yellowstone National Parks—of corner-locked land. [58] Of these corner-locked acres, 74% are on federal lands, and the rest belong to at least eleven states. [59] Roughly half of the corner-locked acres are just one corner-cross away from access, but the other half require crossing multiple corners. [60] These properties share a corner with 11,000 private landowners, [61] of which at least 19% are resource-extraction companies—not ranchers or farmers. [62]

The inaccessibility of corner-locked parcels stems from the legal ambiguities about corner-crossing. Part IV of this Note addresses legal remedies that apply to both isolated and corner-locked public lands, and Parts V and VI focus on solutions specific to corner-crossing.

This Part describes the price society pays when our public lands are inaccessible. The first subpart details the economic opportunity cost to our national and local economies, and the second subpart describes the social opportunity costs to our lives and communities. The third subpart explains why it is critical that this public land is available, recognizing that Americans already enjoy access to millions of public land acres.

Inaccessible public lands represent lost outdoor recreation opportunities, and the economic impact is tremendous. In 2021, outdoor recreation contributed $861.5 billion to the economy and supported 4.5 million American jobs. [63] That same year, BLM lands saw 80.45 million visits, with visitors enjoying 922.8 million hours on federal public land. [64] And 2017 data show that the outdoor recreation industry generated $65.3 billion in federal tax revenue [65] and $59.2 billion in state and local tax revenue, [66] with $45 billion in economic output and 396,000 jobs stemming directly from public lands. [67]

And the outdoor recreation economy is growing at record levels. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this growth as over 10 million additional people have started participating in outdoor recreation since March 2020. [68] The pandemic not only sparked Americans’ desire to be outdoors, but it also provided flexible work options that enabled participation in outdoor recreation. [69] Even more, 2021 data suggest that “outdoor recreation is ‘sticky’; once someone begins to participate, they are likely to continue.” [70] Now, about 54% of Americans—164 million people—participate in outdoor recreation [71] —more than the combined attendance at all NFL, NBA, MLB, and NHL games. [72]

The booming outdoor economy offers diverse, high-paying jobs. These jobs are mainly sustainable resource or tourism based, non-exportable, and predominantly based in rural communities. [73] It is unsurprising that most Western residents across the political spectrum perceive public lands as boosting their state and local economies [74] because data confirms that rural communities with more public lands tend to have improved economies. [75] Indeed, rural counties with the highest share of public lands have lower rates of unemployment and greater personal income growth than counties with less public land. [76] And counties with public land experience more income and wealth per resident. [77] Public lands especially promote small businesses, including thousands of outfitters and guiding companies. Given the undeniable benefits of public lands and the recreation opportunities they offer, the landlocked lands foreclose potential economic growth and development in communities that need it most.

In addition to economic growth, landlocked public lands hinder the social advantages linked to nature access. John Muir, an environmental philosopher, emphasized nature’s role in nourishing the soul: “Everybody needs beauty as well as bread, places to play in and pray in, where Nature may heal and cheer and give strength to body and soul alike.” [78] This idea unites environmentalists, conservationists, and outdoors enthusiasts across the political spectrum. Indeed, nonprofit organizations like the left-leaning Sierra Club [79] and the right-leaning ConservAmerica [80] agree wholeheartedly on one thing: access to the natural world is in the nation’s best interest.

Scientific studies validate these claims. In fact, evidence now connects improved wellness and lower mortality rates with access to the natural world. [81] And research also shows that exposure to nature can mitigate ADHD symptoms; promote social bonding; reduce violence; stimulate learning and creativity; and serve as a buffer to stress, depression, and anxiety. [82] Some further research even suggests that just twenty minutes in nature can reduce stress hormone levels. [83] These benefits have led some health professionals to integrate nature into their treatments. [84] Taking this all into consideration, some environmental groups argue that access to nature is a human right [85] —recognizing that although the “psychological, physical, and cognitive benefits of nature may be universal, . . . access to natural areas is not.” [86]

Even politicians have long recognized the value of ensuring the public’s access to the natural world. In 1965, Congress created the Land and Water Conservation Fund [87] (LWCF) to enhance public access to outdoor areas and thereby strengthen the “health and vitality” of the American citizenry. [88] Echoing Congress in a 1971 special message to it to promote an environmental program, President Nixon said “[Public lands represent] in a sense, the breathing space of the nation.” [89] And in 2019, Congress demonstrated strong bipartisan support for public lands when it permanently reauthorized the LWCF. [90] Public lands are like public schools or public libraries—places to learn, explore, play, and develop—and unhindered, low-cost access to public lands facilitates these enriching experiences. Public lands level the playing field and offer these immense benefits from the natural world to anyone willing to put on a pair of hiking shoes, regardless of their class or socioeconomic status. So it is unsurprising that almost all Western residents use their public lands. In 2022, 88% of Western residents recreated on public lands at least once in the prior year, with an astonishing 68% visiting three or more times. [91]

Although access to public lands provides these social benefits, landlocked public property creates social harms. Obviously, restricted access reduces opportunities for people to experience the benefits these lands provide. But another harm is more insidious. De facto private ownership of these public lands by their adjacent landowners creates a system where the rich get richer to the exclusion of—and paid for by—the lands’ rightful owners.

No business-savvy landowner wants outright ownership of public lands. [92] “That would entail responsibility, stewardship, and worse, the payment of property taxes.” [93] Instead, landowners with neighboring public lands can privately exploit a public resource with the public bearing the costs. [94] Even worse, some landowners near popular public recreational areas sell “trespass permits” that allow recreationists to access the public land via the private, landlocking property—but only after paying a fee. [95] These landowners, by controlling adjacent public lands, profit at the public’s expense. In a time of escalating economic inequality, [96] private dominion over landlocked public lands exacerbates the injustice. Public lands should be a haven for everyone—regardless of income or social status—not a means for landowners to acquire free property to add to their private fiefdom.

The fact that Americans already enjoy access to millions of acres of public land does not diminish the importance of unlocking the public property that is still inaccessible. This subpart lays out two reasons why access to these public lands is critical. First, as outdoor recreation on public lands continues to boom, overcrowding becomes a concern. So unlocking over 16 million acres can ease the burden on the already-accessible public places. And second, much of the landlocked public land is raw, untouched wilderness. These properties offer opportunities for adventure and isolation that are undermined by the manicured trails and man-made infrastructure that accompany many public lands.

Americans are flooding to public lands in record numbers. [97] By all accounts, this increased participation in public land recreation is a good thing. [98] But like the chic new restaurant in town, the growing popularity of our public lands leads to many people waiting in line for a spot to become available. In fact, a quick camping trip to Yosemite National Park—once available to the spontaneous weekend warrior—now requires advanced planning and pre-arranged passes. [99] And some public land campgrounds have become so popular that people are using internet bots to snag reservations as soon as they become available. [100]

Public land overcrowding is not limited to charismatic national parks like Yosemite. Indeed, many public lands are exceeding their “recreational carrying capacity”—the point where there are too many people around to enjoy the experience of being in nature. [101] It is hard to benefit from the enrichment that nature provides when plans to enjoy a peaceful morning hike turn into a battle for parking at the trailhead. Implicit in the allure of recreating on public lands is the desire to experience nature without the constant presence of crowds. So with more people recreating on public lands more often, Americans would benefit from access to more land to visit. To continue the restaurant analogy, everyone would benefit if the owners would open a new spot across town. When it comes to public land, almost 17 million new spots already exist—the owners just need to unlock the door.

Unlocking landlocked public land would not only ease the overcrowding problem, but it would also provide access to unique recreational opportunities. In the West, the landlocked public land consists of myriad ecological landscapes—including grasslands, deserts, forests, and mountains. [102] These landscapes are home to thousands of geographical features that would attract would-be outdoor recreators. [103] These inaccessible features include 691 distinct mountain peaks or buttes, 414 bodies of water, 269 natural springs, and other ridgelines, cliffs, and arches. [104] Along with their inherent natural beauty, these landlocked properties provide another selling point—unrefined wilderness. Places like Yellowstone National Park are undoubtedly beautiful. But they contain a network of paved roads, manicured hiking trails, and charming campsites that are a constant reminder that civilization is nearby. Although these accommodations are often helpful, many outdoor recreators long for a more primitive experience. [105]

Unlocking our landlocked public lands can help provide that experience. These properties are necessarily unadulterated. Because the public cannot access this land, there is no need for the man-made infrastructure that many parks contain. The result is often untouched wilderness. Instead of the “Disney World of National Parks,” [106] these properties offer an experience more akin to how the landscape looked long before mankind made our “improvements.” And these types of experiences provide the solitude, silence, and wildness that refreshes the soul. [107]

This Part discusses common law doctrines that litigants and scholars have offered—mostly unsuccessfully—as remedies to the landlocked public land problem. The first subpart examines easements by strict necessity, and the second subpart examines the public trust doctrine.

On the surface, the most straightforward solution to solving the landlocked public lands problem is through easements by necessity. Easements are property rights that give the owner of one property (the dominant estate) a non-possessory right over another’s property (the servient estate). [108] For landlocked public lands, an effective easement would burden the servient estate (private property) with a right of way for the public to access the dominant estate (the landlocked public parcel). Easements can be created expressly or by implication, and courts recognize two types of easements arising from implication: those from prior use and those by necessity. [109]

Courts generally agree that an easement by necessity is created when: “(1) the title to two parcels of land was [once] held by a single owner; (2) the unity of title was severed by a conveyance of one of the parcels; and (3) at the time of severance, the easement was necessary for the owner of the severed parcel to use his property.” [110] In other words, when a landowner conveys a portion of his lands and retains the rest, the common law presumes that the grantor has “reserved an easement to pass over the granted property if such passage is necessary to reach the retained property.” [111] Courts strictly construe the absolute necessity requirement, and the necessity element is often the focus of easement by necessity litigation. Specifically, most courts will not imply an easement by necessity if another access route to the land exists—however inconvenient or expensive. [112]

Easements by necessity stem from the public policy that property should not be made unusable due to inaccessibility. [113] This public policy aims to “prevent any man-made efforts to hold land in perpetual idleness” that would result if the land were cut off from all access to a public road (or other means of access) by being surrounded by private lands. [114]

At first pass, this doctrine seems like an ideal solution to the landlocked public land issue. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court has already foreclosed easements by necessity as an effective legal remedy here. In Leo Sheep Co. v. United States, [115] the Court addressed whether the government possessed an implied easement to build a road across private land to access landlocked public land. [116] Leo Sheep Company brought an action to quiet title against the government after the government built a dirt road across the company’s land to provide access to landlocked public land. [117] The private land at issue was a legacy of a Pacific Railroad Act grant, and Leo Sheep Company was a successor to the Union Pacific Railroad in its ownership. [118] The government was prompted to build the road after public complaints that the Leo Sheep Company was denying access to the public land or requiring the payment of access fees. [119]

The government based its defense on the “settled rules of property law” that invoke an easement by necessity when a grantor landlocks themselves via a real estate transaction. [120] The Tenth Circuit, in support of the government, concluded that when Congress granted land to the railroad, it implicitly reserved an easement to pass over private property to reach other public parcels. [121]

The Supreme Court rejected the easement by necessity argument and reversed the Tenth Circuit’s decision for two reasons. First, the Court held that even when public land was landlocked, it is unclear the strict necessity easement would include the right to construct a road to a recreational area. [122] Second, and more importantly, the Court held that easements by necessity could not be implied because the government, as a sovereign, could exercise its eminent domain power. [123] The Court noted that the doctrine was only applicable whenever “such passage is necessary to reach the retained property.” [124] But in Leo Sheep, the easement was not a “necessity” because there was another way to access the land—condemnation through eminent domain. [125]

Unwilling to strain the doctrine to situations when a sovereign could get access to its land via condemnation, the Court then turned to what it saw as the “pertinent inquiry”: whether Congress intended to reserve an easement to the federal government when it granted the land to the Union Pacific Railroad in 1862. [126] The Court noted how the Pacific Railway Acts specifically enumerated reservations in the grant, [127] but a reserved right of access was omitted. [128] Given this omission, the Court was unconvinced that Congress intended to reserve access rights across the private land [129] and therefore refused to recognize the implied easement that the government asserted. [130]

The practical implications of the government’s easement-by-necessity argument colored the Court’s holding in Leo Sheep. The Court emphasized how the Tenth Circuit’s holding affected property rights in 150 million acres in the West. [131] And judicially implying easements across those acres would have a “substantial impact” on property rights that vested over a century before the case. [132] The Court highlighted the “special need for certainty and predictability” when dealing with land titles and refused to support the construction of “public thoroughfares without compensation” when the government could provide access without relying on an “ill-defined power.” [133]

All told, Leo Sheep makes it harder for the public to access its landlocked property. Without the ability to gain access through easements by necessity, the government is left with limited options. Voluntary land and easement purchases, negotiated access rights, and condemnation actions will be discussed as potential solutions in Part V.

Some commentators have argued that the common law public trust doctrine (PTD) could be a useful tool in providing access to landlocked public land. [134] But for the reasons detailed in this subpart, the PTD is also unlikely to be effective in unlocking most public land.

The PTD originated in Rome and later found favor in England as an approach to protect public access to tidal waters. [135] In England, a riparian property owner held title to submerged land under a river or lake not affected by the tide. [136] In contrast, the King held tidal land in trust to guarantee that the citizenry enjoyed unimpeded commerce, navigation, and fishing rights. [137] So the private shore owner could not deny the public access to tidal waters. [138]

Both state and federal American common law have acknowledged and expanded the PTD. The Supreme Court first recognized the PTD in 1842 via Martin v. Lessee of Waddel. [139] Then, in 1892, the Court extended the doctrine to cover all navigable waters—regardless of whether the waters were subject to the tide—to facilitate commerce on the United States’ thousands of miles of non-tidal navigable waterways. [140] Over a century later, the Court again extended the PTD to cover tidal waters that were not navigable. [141] While the Court has extended the PTD at a federal level, the state courts have taken the doctrine even further.

Indeed, states have interpreted the PTD to encompass a wide range of public interests. [142] The New Jersey Supreme Court expanded the PTD the furthest in Matthews v. Bay Head Improvement Ass’n. [143] In Matthews, a neighborhood resident wanted access to a local public beach and sued, claiming that the PTD gave him a right-of-way across private property to access the shore. [144] The court agreed and recognized that “[t]o say that the public trust doctrine entitles the public to swim in the ocean and to use the foreshore in connection therewith without assuring the public of a feasible access route would seriously impinge on, if not effectively eliminate, the rights of the public trust doctrine.” [145] In short, a public right to swim in the ocean is stymied if the public cannot access the shore. This interpretation of the doctrine to require “reasonable access” [146] across private land significantly enlarged the doctrine’s scope. State courts could use similar reasoning to provide access to other state-owned landlocked properties. But the PTD’s application is likely limited to state-owned public lands. [147] Even then, few states are likely to accept the broad “reasonable access” interpretation adopted by the New Jersey Supreme Court.

At the federal level, it is likely that the PTD applies only to federal lands that are submerged beneath tidal or navigable waterways. [148] But even if the doctrine applies to non-submerged federal land, both state and federal courts—out of concerns for the reliance interests of private landowners—should hesitate to hold that the doctrine demands public access to those lands. As the Court in Leo Sheep noted, such a holding would implicate legal rights attached to millions of private acres that vested over a century ago. [149] Applying the evolved PTD to those properties would upset the notions of predictability and certainty that property law exists to embolden.

Without common law solutions to the landlocked public land problem, Americans must turn to their legislatures for answers. This Part addresses legislative remedies to unlock public lands.

The Court in Leo Sheep told the government that if it wanted access to its landlocked property, it must buy that access. But before a government agency can buy a property interest, it needs two things: authority and money. This Part discusses legislation that satisfies both needs. The Federal Land Policy Management Act (FLPMA) gives the BLM acquisition authority. And the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) provides the revenue needed to make the purchases.

Before 1976, the BLM’s land-acquisition powers were restricted, as its authority was typically granted by special legislative permission and required Congress to determine specific land parcels to buy. [150] But in 1976, Congress enacted the FLPMA, [151] which granted the BLM general acquisition authority via both eminent domain and negotiated purchases or exchanges. [152] This section will discuss both of those paths.

Although the FLPMA empowers the BLM to use eminent domain for better land access, [153] the statute limits that authority to instances where it is “necessary to secure access to public lands.” [154] This “necessary” requirement suggests stricter conditions on the BLM’s eminent domain authority than the Constitution requires. [155] Still, ensuring access to landlocked properties would likely satisfy the statute’s necessity requirement. [156] Even so, eminent domain should be a last resort to gain access to landlocked property. Condemnation actions are both politically contentious and fiercely litigated. If state and federal governments began a crusade to condemn easements across landlocking private land, the political fallout would result in a pyrrhic victory for outdoor recreationists. The future of thriving public lands hinges on congressional support through adequate funding that requires politicians—and their constituents—to have a positive view toward public land access. Public land enthusiasts should avoid political moves that could lead to contempt and insufficient funding for access, maintenance, and protection of public lands. To maximize the political palatability of public land access initiatives, government agencies should exhaust alternatives to condemnation actions—like negotiated land purchases and transfers—when unlocking public lands.

In fact, the FLPMA also permits the BLM to execute land exchanges and purchases. [157] And voluntary land purchases, like those made in collaboration with nonprofit organizations or state agencies, dodge the controversy tied to eminent domain. For example, the nonprofit Trust of Public Lands bought and then resold property to the BLM in 2017 that provided access to 32,000 previously inaccessible acres in Arizona’s Coronado National Forest. [158] In another case, the BLM partnered with Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks Department to provide access to landlocked BLM property. [159] The BLM also engages in land acquisitions without outside help. In 2021 alone, the BLM funded projects that improved public access in Wyoming, [160] Colorado, [161] California, [162] and New Mexico. [163]

Land swaps, where the BLM trades a parcel of public land for a parcel of private land, help all parties involved. Private landowners usually get lands adjacent to their existing properties, while the government sees cost savings associated with having to pay only for the value differences. And the public benefits by gaining access to previously inaccessible public land. [164]

Although the FLPMA empowers the BLM to acquire land to enhance public access, those acquisitions require sufficient funding. The primary funding source for these purchases is the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF). Established in 1965, [165] the LWCF was designed to use revenues from the depletion of one natural resource (offshore oil and gas) [166] to conserve public lands and waters. [167] And since its inception, the fund has helped gain public access to 5 million acres of public land. [168] The LWCF has been used for three general purposes: effecting federal acquisition of recreational land; supporting state acquisition of recreational land; and funding other federal natural resource-related programs. [169]

The LWCF is not a typical trust fund as is understood in the private sector. For example, although the LWCF Act credits the fund with $900 million annually, Congress historically needed to specifically appropriate these funds for use. [170] The fund was rarely fully appropriated, and by 2019 less than half of the $40.9 billion that had accrued in the LWCF had been used—leaving $22 billion untouched. [171] Even more, the LWCF’s authority to accrue money faced challenges and expired twice before 2019. [172] This rightfully troubled environmentalists and outdoor recreationists, prompting more than 200 conservation groups to urge Congress to reauthorize the LWCF. [173]

But in 2019, Congress made significant changes to the LWCF. First, a 2019 amendment permanently reauthorized the fund and ensured continuous revenue collection. [174] Second, the amendment specified that no less than 40% of the fund must go to state projects and no less than 40% must be used for “federal purposes,” with Congress still deciding the distribution of the remaining 20%. [175] Finally, the amendment required Congress to spend $15 million or 3% (whichever is greater) of the appropriated monies on projects that increase access to public land. [176] Although these changes enhanced the LWCF, Congress still left a hole in the legislation. The amendment permanently authorized the fund to accrue its monies, but Congress retained discretion on appropriating the funds. [177] And money that did not get appropriated did not get spent.

This hole was addressed in 2020 with the Great American Outdoors Act (GAOA), which permanently funds the LWCF at $900 million annually “without further appropriation or fiscal year limitation.” [178] So Congress can no longer hold LWCF monies hostage, and at least $27 million is dedicated each year to increasing access to landlocked lands. [179]

Not all public land access initiatives require land or easement acquisitions. This subpart discusses three tools that federal and state governments are using to increase access to landlocked public land: the Modernizing Access to Our Public Land Act, dedicated personnel assigned to facilitate increased public land access, and short-term access programs.

The Modernizing Access to Our Public Land (MAPLand) Act [180] addresses the lack of modern data for recreational opportunities on public lands. Previously, most agencies identified public land recreational opportunities on paper maps or roadside signage that demarcated campgrounds, hiking trails, and areas open to public hunting. [181] Although some of these details can be accessed in a format compatible with GPS, in most cases it cannot. [182] But, the MAPLand Act mandates certain federal agencies [183] to digitize and publish geographic information system (GIS) [184] mapping data on their websites. [185] This data includes details about easements, reservations, and rights-of-way that may be used to provide access to the federal land. [186]

By digitizing this information, the MAPLand Act illuminates public rights-of-way that were obscure or only available on local paper files. For instance, the USFS alone has roughly 37,000 recorded easements, but only 5,000 are digitized. [187] Making this information readily available aides both the public and agency land managers because it allows the land managers to identify and act upon landlocked areas.

The MAPLand Act empowers public land enthusiasts, conservation groups, and federal agencies by providing comprehensive digital access information. This information unveils previously unknown access points and helps agencies prioritize landlocked areas.

State-level walk-in access programs incentivize private landowners to provide public access through financial benefits. State fish and wildlife agencies administer these programs, which typically involve short-term contracts with private landowners to make private lands available to the public. [188] Although traditionally used only for private land access, some states are leveraging these programs to access landlocked public lands by collaborating with adjacent private landowners. “In Montana, 618,330 acres of landlocked state and federal land were ‘unlocked’ during the 2020 hunting season thanks to the properties enrolled as Block Management Areas.” [189] Similarly in Idaho, 525,115 acres of public land were unlocked in 2019 thanks to landowners participating in the Access Yes program. [190] And the Unlocking Public Lands program in Montana provides an annual tax credit to landowners who provide access across their property to “locked” public land for hiking, birdwatching, fishing, hunting, and trapping. [191]

States are also effectively addressing public land access challenges by appointing specialized staff and creating specific programs aimed at unlocking landlocked public land. For example, Montana created a “Public Access Specialist” role whose primary mandate is to increase access to both state and federal public lands. [192] This dedicated staff member helps Montana prioritize public land access projects by working with landowners and agency land managers. [193] The Public Access Specialist also has the Montana Public Lands Access Network (MTPLAN) program at their disposal. Using this program, Montana helps buy “public access easements across private lands and open landlocked or difficult-to-access public lands for recreation.” [194]

Following Montana’s approach, other states and the federal government should consider similar roles and programs. Here, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Dedicated personnel would facilitate an effective and efficient use of the LWCF instead of scattered, agency-wide approaches that are unlikely to achieve the best return on investment.

This Part will explore the unsettled law related to corner-crossing. It will first explore the scope and magnitude of the corner-crossing debate. Next, it will turn to prior state legislative and judicial action on the issue. Finally, it will examine current corner-crossing litigation in Wyoming federal court and how a 19th-century federal statute could clarify this legal gray area.

The primary opposition to corner-crossing rests in the legal reality that land ownership includes more than just the surface of the land. This is a bedrock principle of American property law: a landowner’s use and enjoyment of their property would be impinged if their ownership rights were limited to the surface. For example, the law governing mineral interests is based on the long-standing doctrine that landowners enjoy subsurface rights. [195] To this end, the landowner owns and controls the airspace above the property (up to a certain limit). [196]

The landmark case United States v. Causby [197] underscored this principle by addressing low-flying planes over private property. The Supreme Court held that the airplanes at issue committed an unlawful taking by occupying the airspace immediately above the property:

[I]f the landowner is to have full enjoyment of the land, he must have exclusive control of the immediate reaches of the enveloping atmosphere. . . . [Thus, a] landowner owns at least as much of the space above the ground as he can occupy or use in connection with the land. . . . [I]nvasions of [that airspace] are in the same category as invasions of the surface. [198]

Few would contest this holding. Indeed, without ownership of the immediate airspace, landowners could not build structures like homes, barns, and fences on their property. [199] And courts have used the Causby rule to combat what most would consider inappropriate incursions of private airspace—like ensuring drones cannot hover uninvited over a private home or car accident scene. [200]

But how does this relate to corner-crossing? Can private property owners really contend that when a hiker steps—for less than a second—through the airspace above an infinitesimally small corner, the hiker is guilty of an “invasion” of the adjacent landowner’s property and a burden on the enjoyment of their land? Apparently so.

Landowners argue that because the corners are “like a point in mathematics . . . without length or width,” corner-crossing necessarily invades the airspace of the private property. [201] Indeed, the United Property Owners of Montana website claims, “To cross a corner, a member of the public must cross all four corners, including the private ones. That is a trespass—a physical occupation of private property.” [202] Therefore, they say, “[t]here is no ‘minimal’ amount of trespass that wouldn’t be considered taking of property.” [203] In short, these landowners assert, the government cannot allow the public to corner-cross over private property corners. That, they claim, would be an unconstitutional “taking” of private property. [204]

The legality of corner-crossing remains uncertain as states struggle to pass clarifying legislation and local law enforcement maintain discretion on whether to prosecute corner-crossers. Inconsistent court cases and failed legislation have cemented corner-crossing in a legal gray area.

For example, Wyoming is ripe with legal controversy on the subject. In 2003, a Wyoming hunter was cited for trespassing for corner-crossing after locating the corner with help from a GPS device. [205] After a bench trial, the hunter was found not guilty of the charge “Trespass to Hunt” in violation of a state game and fish law [206] because he had not entered the property (or its airspace) to hunt, fish, or trap “upon the private property,” but sought only to hunt on public land. [207]

The next year, the Wyoming Attorney General’s Office issued a memorandum that declared that the hunter’s trial had “no binding effect on any court.” [208] The memorandum stated that although the hunter did not violate the Trespass-to-Hunt statute, other corner-crossers might violate the criminal trespass statute. [209] According to the attorney general, a corner-crosser could be charged under the Wyoming criminal trespass statute because the legislature had made it clear that landowners own the airspace above the ground, and “the [criminal statute’s] definition of ‘enter’ is expansive enough to include penetrating an invisible plane.” [210]

State legislatures have tried—and failed—to clarify the legality of corner crossing. In 2011, the Wyoming House of Representatives considered a bill that would have legalized corner-crossing if private lands or improvements were not touched, but that bill did not make it beyond committee. [211] A similar bill in Montana also died in a House committee in 2013. [212] Yet another bill was introduced to the Nevada Assembly in 2017, but “[n]o further action [was] taken.” [213] Also in 2017, another Montana corner-crossing bill was introduced. [214] But this time—just four years after attempting to legalize corner-crossing—the bill intended to make corner-crossing a misdemeanor punishable by up to six months in jail. [215] That bill also died in a House committee. [216]

In Montana, more trespass cases reinforce the legal ambiguity of corner-crossing. Indeed, Montana authorities charged Cody Cherry, a Montana citizen, with trespassing on two separate occasions after he corner-crossed twice on the same ranch. [217] The first set of charges were dismissed largely because of imported reasoning from a county attorney’s opinion in another case that claimed that “[i]t was not trespassing to go from one section of public land to the next over that infinite corner.” [218] In his second case, Cherry was found guilty of trespass after walking on eighty feet of private property between public parcels. [219] This stretched the definition of “corner” a bit too far.

In sum, courts in different states found hunters not guilty of trespass after stepping over property corners, an attorney general memo declared that corner-crossers may violate the state’s criminal trespass statute, and three states introduced—and failed to pass—legislation intended to clarify the legal status of corner-crossing. No wonder there is so much uncertainty on this issue.

Against this backdrop of inconsistent and nebulous legal history rests ongoing litigation involving corner-crossing hunters. The case has gained national attention as a topic of hope and controversy in the outdoor community.

In 2021, four out-of-state hunters from Missouri corner-crossed in Wyoming on their way to elk hunt on nearby BLM land. [220] The hunters did not touch private land. [221] Instead, they used an A-frame ladder to cross the private fence without touching either the fence or the private property. [222] But in climbing up one side of the ladder and down the other, they crossed through the airspace of the other two parcels meeting at the point. Unfortunately for them, the private parcels were part of the 23,277-acre Elk Mountain Ranch—owned by North Carolina businessman Fred Eshelman. [223]

Before their hunt, the hunters spoke with local law enforcement about their plan to corner cross near the Elk Mountain Ranch. [224] Both a local police deputy and a Wyoming Fish and Game warden told the hunters that they would not be charged with trespassing. [225] Indeed, despite the ranch manager’s lobbying for a citation, [226] both a Wyoming Game and Fish Department warden and a local sheriff’s deputy refused to cite the hunters after conducting an on-site investigation of the incident. [227] Several days later, however, the apparent influence of Eshelman’s money kicked in, and the Carbon County Attorney instructed that the men be cited for criminal trespass. [228]

The resulting litigation has all the markers of a case that can draw outside attention to the corner-crossing issue. Consider the classic David-and-Goliath fact pattern. An out-of-state multi-millionaire and ranch owner uses his outsized money and influence to keep working-class outdoor recreationists from accessing their public land—claiming the public land for his use only. All of this when the hunters neither touched nor harmed the private land. Facts like these show the inequities that criminalizing corner-crossing can promulgate and should cause the average person to consider the corner-crossing issue more closely. [229]

At the close of the criminal trial, a jury returned not-guilty verdicts for all four hunters. [230] In some sense, the not-guilty verdict is an example of jury nullification. Indeed, the law governing property rights over the immediate airspace is clear: a landowner has the right to exclude others from the airspace directly over their property. The 2004 Wyoming Attorney General memo was unequivocal about that. [231] And the hunters crossed at least a portion of the Elk Mountain Ranch airspace. So this small victory for four out-of-state hunters could be a sign of changing headwinds in the public sphere concerning corner-crossing. Fortunately for those interested in the law about corner-crossing, this case did not stop after the criminal trial.

With the criminal trial still pending, Eshelman filed a trespass civil action in Montana state court, seeking damages and a declaratory judgment that corner-crossing is trespass as a matter of law. [232] The defendants removed the case to federal court. [233] After the federal district court denied the plaintiff’s motion to remand to state court, Eshelman’s attorney signed a disclosure statement alleging damages of up to $7.75 million stemming from the hunters’ corner-crossing. [234] This case sets up a battle between two competing legal doctrines. In one corner, the right for landowners to control their airspace. [235] And in the other corner, a 135-year-old federal statute that proscribes enclosing federal public land—the Unlawful Inclosures Act. [236]

The Unlawful Inclosures Act should abrogate state-law trespass claims involving public land corner-crossing. “Generally speaking, state law defines property interests.” [237] But through the Property Clause, [238] Congress possesses plenary power over federally owned public lands. [239] Indeed, the Supreme Court, in assessing Congress’s plenary power, has observed that “[t]he power over the public land thus entrusted to Congress is without limitations.” [240] In fact, Congress’s powers under the Property Clause are broad enough to extend beyond the public land borders “to regulate conduct on private land that affects public land.” [241]

Although state and local governments typically share legal authority with Congress over federal land, state and local powers “must yield under the Supremacy Clause when they conflict with federal law.” [242] Indeed, “federal legislation, together with the policies and objectives encompassed therein, necessarily override and preempt conflicting state laws, policies, and objectives under the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause.” [243] So where Congress has enacted federal legislation concerning the protection, use, or acquisition of public lands, conflicting state laws—as well as private claims relying on state laws—must yield to federal law. [244]

The federal law implicated by this corner-crossing issue is the Unlawful Inclosures of Public Lands Act of 1885 (UIA). [245] Congress enacted the UIA in response to the “range wars” between 19th-century cattlemen. [246] Throughout those range wars, cattlemen would build fences around public lands to exercise monopoly control over—without possessing a legal claim to—swaths of public land. [247] To curb these exclusionary practices, Congress enacted the UIA to proscribe “all ‘enclosures’ of public lands, by whatever means.” [248] The UIA reads, in relevant part:

All inclosures of any public lands . . . heretofore or to be hereafter made, erected, or constructed by any person, party, association, or corporation . . . are hereby declared to be unlawful, and the maintenance, erection, construction, or control of any such inclosures is hereby forbidden and prohibited[.]

No person, by force, threats, intimidation, or by any fencing or inclosing, or any other unlawful means, shall prevent or obstruct . . . any person from peaceably entering upon . . . any tract of public land subject to . . . entry under the public land laws of the United States, or shall prevent or obstruct free passage or transit over or through the public lands[.] [249]

The Supreme Court first construed the UIA in Camfield v. United States, [250] a case in which the government charged defendant landowners with violating the UIA. [251] There, the defendants placed fences on their private property, “manifestly intended to enclose the Government’s lands, though, in fact, erected a few inches inside the defendants’ [private] line.” [252] The defendants thus enclosed 20,000 acres of public land to carry out irrigation projects on their parcels. [253] They admitted to the fencing scheme, but argued that the UIA was unconstitutional if it applied to fences located on private land. [254]

The Court disagreed. [255] It concluded that Congress’s powers to protect and control the use of its own lands must include prohibiting landowners who owned or controlled the alternate sections in the checkerboard to enclose the entire tract. [256] The Court analyzed the fence from the perspective of nuisance law, noting that though a landowner may generally do as they please with their property, “[h]is right to erect what he pleases upon his own land will not justify him in maintaining a nuisance.” [257] To this end, the Court went on to announce what has become the UIA test:

So long as the individual proprietor confines his enclosure to his own land, the Government has no right to complain, . . . but when, under the guise of enclosing his own land, he builds a fence which is useless for that purpose, and can only have been intended to enclose the lands of the Government, he is plainly within the statute, and is guilty of an unwarrantable appropriation of that which belongs to the public at large. [258]

Early cases following Camfield elaborated the scope of the UIA. In the first notable case, the Eighth Circuit held in Mackay v. Uinta Development Co. [259] that the UIA did not require a fence or a physical structure to support a cause of action. [260] Instead, a mere threat of a trespass claim was enough to violate the statute. [261] Mackay required the court to analyze a trespass claim brought by a landowning company against a sheep farmer. [262] The company owned all the odd-numbered sections in a tract of land that included at least 300 square miles (192,000 acres). [263] Almost all the even-numbered sections in the tract were public land. [264]

Mackay was a sheep farmer whose spring and summer ranges were north of that tract. [265] His wintering lands, however, were to the south of the tract on an unbroken parcel of public land. [266] The onset of winter required Mackay to shepherd his sheep across the tract that included the plaintiff’s odd-numbered sections to the public-land wintering range where he was permitted to graze his sheep. [267] The company warned Mackay not to cross its lands. [268] In essence, the company asserted the obvious—Mackay could not drive his sheep across the tract without either himself or his sheep trespassing on many private, odd-numbered sections. When Mackay refused to heed the company’s warning and started across the tract with his sheep, the company had him arrested and filed a civil suit for trespass. [269]

If this fact pattern sounds familiar, it is because it is similar to the pending civil case against the hunters at Elk Mountain: defendants have an implied license from the government to use public land for a lawful purpose, and a wealthy private landowner is—under the color of state trespass law—attempting to gain exclusive use and control over public land by preventing corner-crossing.

Mackay claimed the right to herd his sheep over the publicly owned sections without subjecting himself to a charge of trespass and used the UIA as a defense to his crossing. [270] The company conceded Mackay’s right to the public domain—in theory [271] —but threatened to prosecute him with trespass if he entered the odd-numbered sections. “If the position of the company were sustained,” the court noted, “[n]ot even a solitary horseman could pick his way across without trespassing.” [272] Today’s corner-crossing litigation directly implicates the court’s hypothetical solitary horseman.

The court acknowledged that this case created a conflict between competing rights: the landowner’s private property rights conflicted with the public welfare. [273] But it also recognized that Camfield dealt with this same conflict and determined that legislation like the UIA can be constitutional, even if it weakens “absolute rights of private property.” [274] In line with Camfield, the Eighth Circuit thus recognized that the UIA “prohibit[s] every method that works [as] a practical denial of access to and passage over the public lands.” [275] In other words, fences or other physical structures are not required to unlawfully enclose public land. Indeed, the mere threat of a civil trespass action can violate the UIA. The court held that the UIA entitled Mackay to cross over the checkerboard tract without violating trespass laws: “all persons . . . have an equal right of use of the public domain, which cannot be denied by interlocking lands held in private ownership.” [276]

The same year, the Eighth Circuit further developed the UIA doctrine. In Stoddard v. United States, [277] the court affirmed the trial court’s order for the defendant to remove a fence on private land that obstructed the free passage of livestock to public land. [278] The defendant argued that section 3 of the UIA limited the UIA’s reach to people and did not guarantee access to animals. [279] The Stoddard court refused to adopt the limited “persons only” reading of the UIA and concluded that the UIA “was intended to prevent the obstruction of free passage or transit for any and all lawful purposes over public lands.” [280] The free passage of hikers, hunters, campers, and outdoors enthusiasts (and the animals that join them) is a lawful purpose for which the public may seek access to public lands.

More recently, in United States ex rel. Bergen v. Lawrence, [281] the Tenth Circuit analyzed the UIA and relevant case law and affirmed the UIA’s broad power to protect access to public lands. The issue in Bergen was whether a defendant-landowner could construct a fence on his property without following government requirements. The defendant erected an “antelope-proof” fence on his property—defying BLM standards—that denied antelope access to critical wintering habitat on public land. [282] The trial court found that the fence violated the UIA and ordered the defendant to either remove the fence or modify it to conform to BLM standards. [283] The Tenth Circuit affirmed. [284] In doing so, the court in Bergen provided guidance for UIA claims that applies to today’s corner-crossing litigation in two important ways.

First, Bergen acknowledged the UIA and the early cases that helped create the UIA doctrine are still good law. [285] Aside from the obvious reasons why this is important, the Bergen court imported the Eighth Circuit doctrine into the Tenth Circuit. This helps clarify whether the pre-1929 Eighth Circuit UIA decisions are binding on today’s Tenth Circuit. [286] Notably, four of the six states that comprise the Tenth Circuit hold almost half of the total corner-locked acreage in the country. [287]

Second, the court in Bergen held that the district court’s order requiring that the fence be removed or modified was not a “taking” that required compensation. [288] Indeed, the court observed that “[a]ll that [defendant] has lost is the right to exclude others, including wildlife, from the public domain—a right he never had.” [289] This nullifies the corner-crossing opponents’ argument that “[t]here is no ‘minimal’ amount of trespass that wouldn’t be considered taking of property.” [290]

In summary, the UIA and subsequent cases that developed its meaning have left today’s courts with the following doctrine: (1) The federal government has plenary power to regulate private property to protect access to its own lands. [291] (2) Fences or other physical barriers are unnecessary to violate the UIA. Indeed, mere threats of trespass prosecution suffice. [292] (3) The UIA is not limited to “persons” and was enacted to prevent landowners from denying free passage for “all lawful purposes over public lands.” [293] And (4), requiring a private landowner to remove a barrier denying access to public land is not a “taking” that requires compensation. [294]

The UIA does not implicate the same reliance interest concerns as the common law solutions because at the time of the grants, landowners understood that the public could cross corners. It has been private action—not the law—that has evolved. This is shown by Justice Thurgood Marshall’s questioning during the Leo Sheep oral argument:

[I]s it not true, if you look at the checkerboard that it would always be possible to stay on government land except where you have to cross at corners? . . . So is it not possible that Congress—you mentioned the widespread understanding that people could go anyplace they wanted to in those days without worrying about having somebody build a fence in front of them. Is it not likely that Congress did not dream that there would be any problem about cutting across a corner every mile or so? [295]

The UIA has been on the books since 1885—just a few years after the transcontinental railroad was completed. [296] And early cases like Mackay made it clear that the UIA abrogated state-law trespass claims for corner-crossing. [297] So if there are any reliance interests at stake here, it is the interest of the public to lawfully cross at the public corners, not of the landowner to “exclude others . . . from the public domain—a right he never had.” [298]

The Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission, in a 1962 report to the President and Congress stated: “It seems unnecessary to defend the right of the public to enter upon its own property unless such entry constitutes a hazard to the visitors or to the resource . . . .” [299] Yet here we are, sixty years later, defending that right, as more than 16 million acres of public land lie out of the public’s reach. Not that progress has not already been made. In fact, as recently as 1986, some estimated that between 80 and 120 million acres of public land were inaccessible. [300] But this progress is no reason to lose urgency in unlocking the rest of America’s landlocked property.

The common law has been unable to offer meaningful solutions to this problem. The Court in Leo Sheep refused to allow the BLM to acquire private property through an implied easement arising from necessity. [301] And the Public Trust Doctrine is just as unlikely to provide access across private land to landlocked public parcels. [302] But Congress and state legislatures have recently stepped up to facilitate land and easement acquisitions that have slowly chipped away, parcel-by-parcel, at unlocking our public lands. [303]

This Note takes the next step and offers a unique solution—specific to the special issue of corner-crossing. The UIA has long been overlooked as a federal remedy to state-law trespass claims related to corner-crossing. Indeed, if the UIA and its progeny are properly understood and applied, 8.3 million acres of corner-locked property could be made publicly accessible in one fell swoop. This would be an enormous win for outdoor recreationists and the American public. This land is your land. It is time that the law treats it as such.