Abdul Jamil Urfi revisits how environmentalism evolved from a top-down conservation approach to grassroots activism.

Born in the 1960s, I belong to a generation that witnessed the evolution of the environment movement in India.

As a child, I remember reading articles on wildlife in magazines such as the Illustrated Weekly of India. They buttressed the point that breathtaking wildlife existed in the jungles of India and needed to be preserved for posterity. This was conservation from the top, led by a number of old landlords and ex-civil service officers from the British Raj, many of whom had been game hunters (shikaris) in their youth but had reformed to become devoted conservationists.

Meanwhile, important events were happening worldwide. The Stockholm Declaration in 1972 followed by the Brundtland Commission Report in 1987 and the ‘World Commission on Environment and Development’ (WCED) were making waves. These gave birth to ideas such as ‘precautionary principle’, ‘assimilation capacity’, ‘polluter pays principle’, ‘public trust doctrine’, ‘inter-generational equity’ and ‘sustainable development’, terms that were to gain currency in the years to come. Picked up by activists and journalists at home, these international developments had a trickle-down effect on India. It was no more just a question of beautiful wildlife or idyllic landscapes. Human communities came into the picture too.

Being a birdwatcher, I travelled into the countryside quite often and soon my interest in birds transitioned into a concern about the fate of their habitats. Just like missionaries advocate shunning vices and living an austere life, we conservationists propagated messages like ‘Give up shikar ’, ‘Don’t kill animals’.

Here’s how a typical conversation with a villager would go (we were mostly dressed in western clothing and were referred to as sahib — an old colonial term for a British officer):

“ Ram Ram (greetings) sahib , what are you doing?”

“ Hum chidiyon ki padhai karte hain. (We study birds).” We would be amused at their reaction, which couched something like: “They come all the way from the city just to see these birds? Don’t they have anything better to do?’

Similarly, to the question if local people killed birds for food or shikar , sometimes the answer would be, ‘Why not?’ The simple villager did not see things in the way we expected them to. Come to think of it, from their perspective, killing birds for meat or stealing their eggs were for survival.

The unique problems in conservation faced by developing countries can be well illustrated by the controversy over cattle grazing at Keoladeo Ghana Bird Sanctuary in Bharatpur, Rajasthan. The sanctuary’s rich biodiversity and conservation significance are well known but a totally different picture emerges when you flip the coin. The park also happens to be the only grazing ground for thousands of cattle belonging to farmers from 14 nearby villages. In the arid, hostile wilderness of the Rajasthan desert, competition for scarce resources makes this park a battleground.

In the 1980s some well-meaning scientists, ornithologists and conservationists, headed by a Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) team under its charismatic ornithologist director Salim Ali, appealed to the Indian government to enforce a ban on cattle-grazing to make Keoladeo an inviolate space for birds, particularly for the highly endangered migratory Siberian crane which used to winter in the park.

For centuries, the villagers had grazed their cattle in the park without any objection from the rulers of the princely state of Bharatpur, whose ancestors had created the park as a private hunting preserve. But with this ban, enforced with all the might of the state, the villagers were incensed. There were numerous clashes between locals and the police and park officials, and several people died in this pitched resistance battle. Newspapers questioned: ‘Is Bharatpur for birds only?’ (Similar questions were raised when Project Tiger was kicked off in the 1970s).

The 1980s saw interesting developments in the environment protection movement. It was also a time before the liberalisation of the economy and globalisation when the intelligentsia was yet to warm up to private enterprise and industry. I recall a conversation with a highly placed friend, who commented cynically on a TV advertisement of a new motorcycle with a tagline “Fill it, shut it, and forget it”. The biker in the advertisement roared with his machine into the countryside, on a long and winding road into forests and hills. “Look at the attitude of the greedy capitalist class which wants the environment and wildlife to be preserved so that only they and their children can enjoy it," my friend said angrily.

The environment versus development debate hogged the headlines. At the height of the campaign to protect the Silent Valley forest from the construction of a dam across the Periyar river, I remember politicians from Kerala saying that development was more important than the environment because people want jobs, a better lifestyle and livelihood. They maintained there was nothing wrong if tropical evergreen forests of the Silent Valley are cut down to make way for the dam.

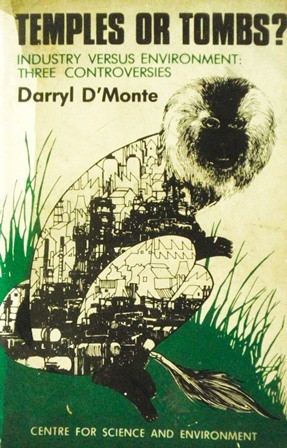

Environment journalist Darryl D'Monte examined the politics behind the Silent Valley dam and other industries versus environment controversies in his book ‘Temples or tombs?’, where ‘temple’ alluded to India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s reference to industries and dams as temples of modern India, signifying progress and modernity. Whether these temples spelt doom for the environment was the core concern of the book. Interestingly, the cover of the book had an outline of the lion-tailed macaque — a species of monkeys endemic to the Western Ghats of India — that would be affected if the proposal to build the dam at Silent valley came through.

During this time, the manner in which people wrote about the environment was changing. The first signs of change was the first citizens report on India’s environment compiled by Anil Aggarwal and his team at the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE).The project was inspired by environmental movements in other countries, notably in south east Asia.

We read about the ‘Chipko Andolan’— a grassroots level movement started by women in the Himalayan district of Chamoli who hugged the trees to protect them from being cut by a sports goods manufacturing industry (chipko is Hindi for hug). Unconventional but important questions were being asked, for instance, how many miles does a village woman have to walk to fetch enough firewood to cook her day’s meal or to collect enough water for the family’s daily needs? The message was clear: it is in people’s interest that the forests remain.

The conflicts between different types of social realities were becoming increasingly apparent. The gap between rural hinterlands and urban areas — the proverbial ‘Bharat-India’ divide — was more pronounced. Later, writers attempting to develop a theoretical structure of environmental studies in India were to supply interesting terms such as ‘ecosystem people’ for those living in the rural hinterland and ‘global omnivore’ for people living in urban areas and enjoying a high (energy) consumption lifestyle and heightened consumer choices.

Such reportage also forced a new type of thinking about people and the environment in general. The so-called elite conjured up an image of poor, rural folks as criminals harming the environment. For instance, cow dung, which ought to have been returned to the earth for recycling and making the soil fertile was being burnt by them as dung cakes. India’s then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi made a famous statement at an environment conference of the United Nations saying, ‘Poverty is the worst polluter’, which in hindsight appears politically incorrect.

In the middle of all these developments, how did academic institutions, colleges and research departments in Universities react? The short answer is by cocooning themselves in their ivory towers.

Some examples from pollution studies, which formed the bulk of presentations in seminars and meetings highlighting environmental conservation, are illustrative. A huge amount of toxicological research was being published from the biology and chemistry departments of Universities, estimating lethal dose (LD50 studies) on a variety of animals and plants. Much of it, grey literature, went into oblivion for the lack of clarity about the real issues and poor experimental designs. The only purpose they served was getting people their PhDs and jobs, and mouthing platitudes about the environment.

A recent article by an Indian Institute of Technology professor, Milind Sohoni, rightly pointed out that the training in our elite institutions and the national curricula does not empower ordinary students to probe their lived reality. Rather, it perpetuates a ‘peculiar intellectualism’ divorced from the community in which these institutions are embedded. No one, at least in academic circles, seemed to question seriously the fact that most chemical toxins were being dumped in rivers by industries and not so much by the local people, whose wastes were mostly organic and of a biodegradable kind.

The author is an associate professor of environmental studies at the University of Delhi. He is writing a book on his experience as a biologist in India.